First Published in Dressage and CT, August 1995

The Alexander Technique and Classical Equitation

by Elizabeth Reese

"If we communicate with all the sensitivity we are capable of, then the horse will understand." - Nuno Oliveira

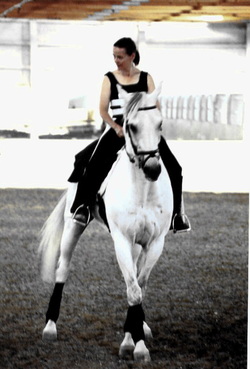

The principles of the Alexander Technique are fundamentally the same as those of classical equitation. Both focus on achieving integrated and supple movement, without the use of force, through the delicate exploration of balance. Through the study of the Alexander Technique, a rider can increase his kinesthetic awareness of lightness and understand how to quiet his nervous system in order to meet the sensitivity of the horse's. Riding can become a dialogue about balance and mobility and the delicate play between these two things.

F.M. Alexander studied the way in which we, as humans, use ourselves. He applied to humans what has been known for centuries in the training of horses: that the dynamic relationships between the head, neck, and back are the primary factors in organizing movement. In the use of ourselves, Alexander included how we use our minds as well as our bodies and that it was virtually impossible to separate one from the other. How we think is a reflection of how we perceive as well as how we move and vice versa. By using gentle manipulations and verbal guidance, he taught students how to overcome their habitual reactions in order to function with greater efficiency and ease.

Alexander discovered that the head/neck region is a primary place of tension and habitual compression and was indicative of compression in the rest of the spine. In an Alexander lesson, in order to release any downward compression on the spine, a person is directed to allow the neck to be free in order to let the head move forward and up (into its correct anatomical relationship to the spine) and to allow the back to lengthen and to widen. Students of the technique often describe an experience of moving with far greater ease and lightness than they've ever experienced before.

Posture, as defined in the Alexander Technique, is not about holding one's body in a specific shape. Rather, it is about balance, which, by its nature, is ever-fluctuating. To attain balance, a person needs to be taught to "release superfluous muscular tension and return to a resting state in which the muscles are lengthening" (Alexander, The Use of the Self). In Misconceptions and Simple Truths in Dressage, Dr. H.L.M. van Schaik states that:

"The teachings of the Alexander Technique have confirmed in me the conviction that only by making one's self tall and by using the abdominal muscles, can one be secure, light and still on a horse and able to create impulsion. . . The Alexander Technique taught me that the head has to be balanced.. . On a horse, one should avoid any kind of rigidity; correct riding entails the rider reacting to what he is feeling, and being rigid makes feeling what is going on with the horse impossible. Therefore, balance your head; do not force it up."

A student of the Alexander Technique can develop a refined sense of balance. By allowing the body to be free of any downward pressures and contractions and letting the joints move into their optimum freedom, a rider can easily follow the movements of the horse. In addition, any action that the rider does make can be both intentional and momentary.

The Manual of Equitation of the French Army for 1912 states that "A good seat results from a general de-contraction, particularly from the suppleness of the loin... Fixity on horseback is the absence of all voluntary or useless movements and the reduction to the minimum of those that are indispensable." The reason to discover a quiet seat is so that we can listen. We must first find a place of quiet listening in order to act. Without listening, all of our actions are really reactions.

The task of the rider is to become aware of how his or her own actions cause reactions in the horse. The rider needs to discover a neutral place where she or he is not interfering with or disrupting the horse's balance. This is what a good seat is. If you act with the right hand and you don't know what the left is doing, you could be involuntarily asking for what you don't want. A horse cannot make these distinctions. A horse can only respond to your actions or not respond to your actions (the former being the most desirable, because that is where training begins). The more conscious each action becomes and the less a rider interferes, the more brilliantly the horse will move.

In learning to ride, a student needs to overcome his instinctive reflex responses and replace them with new patterns of learned responses. For example, a beginner needs to learn to sit up and not pull. All new riders (and quite a few experienced ones) have the overwhelming urge to lean forward and pull in the name of balance and control; yet because pulling and falling forward have disastrous effects on the balance of both horse and rider, this loss of control becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The rider's loss of balance reinforces his fear, and he then grabs on harder and leans further forward. It can become increasingly difficult for a rider to get out of this cycle. The only way to learn a different response is to make a change before this ingrained reaction kicks in.

One of the greatest aids in this process is what Alexander called "thinking in activity." By this he meant having a conscious awareness of what one is doing and, at the crucial moment before committing to the habitual reaction; making a clear decision to do something differently. The riding student must first be made aware of what is unconscious, and usually unnecessary and disruptive, movement Secondly, he must decide not to do that movement (i.e., lean forward when the horse increases in speed). And thirdly, he must allow his body to stay back. I use the word "allow" because if he muscularly forces himself to stay back he becomes instantly rigid and can no longer follow the movements of the horse.

The body responds to a given stimulus so quickly that we often react before we know we've reacted. To decide to change the course of things is no small charge. It requires exploring unknown territory. We cannot rely on former experiences and feelings, rather, we must rely on principles. If we rely solely on whether something "feels right," then we condemn ourselves to repeat the same habitual movements over and over again. "People don't do what they feel to be wrong when they are trying to be right" (Alexander, The Universal Constant in Living). Instead, we can learn to put our trust in our thinking, pausing instead of reacting, and deciding to follow a different course of action, regardless of how it might feel. In this way, we open the door to new possibilities. Alexander called this approach "keeping in touch with your reason."

If it is difficult to check one's reactions in general, it is nearly impossible when a person's or a horse's system is anything but calm. "In anxiety states, there is no such control: there is a state of tense preparedness which is liable to discharge excessively when the organism is stimulated; and in this state, all manner of aspects of the environment are noticed and reacted on, which would be ignored in a less tense state" (Frank Pierce Jones). Or, as Joyce Warrack said, "No instrument is as unmanageable as the human organism in a panic" (article: "The Indirect Approach to Singing"). Cultivating calmness is the task of both the rider and the trainer. Good humor is an invaluable aid. "Progress does not come from the movement itself but from the manner in which it is executed" (Manual of Equitation from the French Army, 1912).

Both the Alexander teacher and the rider communicate through the use of their hands. A beginner learns not to pull. An intermediate rider learns to leave his hands alone. An advanced rider learns to give with his hands. "Between fixed and pulling, there is a world" Nuno Oliveira). If I am not moving my hands in space, but I am still tensing every muscle in my forearm, it is still a pull. In describing the Alexander Technique's use of hands-on manipulations, Frank Pierce Jones, an early practitioner, said, "One of the basic principles of the technique seems to be that the amount of kinesthetic information conveyed is in indirect proportion to the force used in conveying it" This statement parallels Nuno Oliveira's description of using the hands in riding: "To fix is not pulled. It is adjusted. It remains tranquil. The hand has to be a filter, not a cork or an open faucet." Learning to give with the hands is a lifelong pursuit.

To pull or to push a horse into place constitutes force. Horses are no different than people in the fact that if one moves them with force, then they learn that it takes force to be moved. But if one asks with an ever-increasing delicacy, what we call "tact”, then we can communicate to the horse in the most refined and elegant ways. "The mark of good training," said Oliveira, "is the maximum each horse is capable of without force." The fact that a person does not need to employ force in order to ride is, for some reason, a very difficult concept for any of us to grasp. If a rider uses muscular force, the horse will meet that force with a corresponding resistance. This is a simple reflex: if you push against someone, he or she will push back; if you pull, he or she will pull back In addition, when the rider contracts the muscles of the leg to apply force, there is a disruption in the balance and ease of the seat.

Alexander maintained that "Man is a psycho-physical whole... he is a unified whole." Living creatures do not function in parts. The part is always a reflection of the entire system. In Basic Equitation, Commandant Jean Licart states, "It should be noted that because of the horse's muscular interrelationships, the forward and rear springs are in one piece. One of them can not be compressed without compressing the other; and if one of them is released, the other is too. We should not be so determined to get a specific result or movement that we compromise the use of ourselves or of our horses. "No matter how many specific ends you may gain, you are worse off than before, [Alexander] maintained, if in the process of gaining them you have destroyed the integrity of the organism" (Frank Pierce Jones). How we get somewhere is more important than whether or not we arrive.

In my experience, one of the benefits of studying the Alexander Technique and classical equitation simultaneously is that the principles of the two worlds reinforce each other. Riding from this approach becomes effortless. The horse and the rider learn to move with greater freedom. Lightness is a tangible and sustainable result.

When I apply the principles of the Alexander Technique, allowing my neck to be free in order to allow my head to move forward and up and my torso to lengthen and to widen, and if I include my limbs in this action, allowing my hands to move away from my back, the horse will have an immediate corresponding action, his back widening, his head releasing at the poll, his neck moving out with freedom. No matter how refined or complicated I become in my demands of the horse, if I return to this place of simplicity, the execution of the movement is done with ease and moves towards better integration for both of us. In addition, if the horse begins to drop his haunches underneath him and releases his jaw, his back becoming round, I experience the movement in my own body as though an Alexander teacher's hands were on me giving clear directions of energy moving up my spine, my head moving forward and up, and my back lengthening and widening.

Riding is "more about intelligence and feeling than muscle and strength" (Jean Saint-Fort Paillard, Understanding Equitation). The question is how small an effort can I make? The discovery is about the difference between control of movement and freedom of movement. The two studies continue to reinforce and illuminate each other. And in meeting the sensitivity of the horse, I find an ever-increasing delicacy and balance in myself so that the dialogue becomes a whisper, a thought a glance.

Elizabeth Reese is a graduate of the American Center for the Alexander Technique. She maintains a practice in Sugar Loaf, New York and in New York City where she is on faculty at ATNYC. She is also a student and teacher of classical equitation.

copyright 1995 Do not reprint without permission from the author.

The Alexander Technique and Classical Equitation

by Elizabeth Reese

"If we communicate with all the sensitivity we are capable of, then the horse will understand." - Nuno Oliveira

The principles of the Alexander Technique are fundamentally the same as those of classical equitation. Both focus on achieving integrated and supple movement, without the use of force, through the delicate exploration of balance. Through the study of the Alexander Technique, a rider can increase his kinesthetic awareness of lightness and understand how to quiet his nervous system in order to meet the sensitivity of the horse's. Riding can become a dialogue about balance and mobility and the delicate play between these two things.

F.M. Alexander studied the way in which we, as humans, use ourselves. He applied to humans what has been known for centuries in the training of horses: that the dynamic relationships between the head, neck, and back are the primary factors in organizing movement. In the use of ourselves, Alexander included how we use our minds as well as our bodies and that it was virtually impossible to separate one from the other. How we think is a reflection of how we perceive as well as how we move and vice versa. By using gentle manipulations and verbal guidance, he taught students how to overcome their habitual reactions in order to function with greater efficiency and ease.

Alexander discovered that the head/neck region is a primary place of tension and habitual compression and was indicative of compression in the rest of the spine. In an Alexander lesson, in order to release any downward compression on the spine, a person is directed to allow the neck to be free in order to let the head move forward and up (into its correct anatomical relationship to the spine) and to allow the back to lengthen and to widen. Students of the technique often describe an experience of moving with far greater ease and lightness than they've ever experienced before.

Posture, as defined in the Alexander Technique, is not about holding one's body in a specific shape. Rather, it is about balance, which, by its nature, is ever-fluctuating. To attain balance, a person needs to be taught to "release superfluous muscular tension and return to a resting state in which the muscles are lengthening" (Alexander, The Use of the Self). In Misconceptions and Simple Truths in Dressage, Dr. H.L.M. van Schaik states that:

"The teachings of the Alexander Technique have confirmed in me the conviction that only by making one's self tall and by using the abdominal muscles, can one be secure, light and still on a horse and able to create impulsion. . . The Alexander Technique taught me that the head has to be balanced.. . On a horse, one should avoid any kind of rigidity; correct riding entails the rider reacting to what he is feeling, and being rigid makes feeling what is going on with the horse impossible. Therefore, balance your head; do not force it up."

A student of the Alexander Technique can develop a refined sense of balance. By allowing the body to be free of any downward pressures and contractions and letting the joints move into their optimum freedom, a rider can easily follow the movements of the horse. In addition, any action that the rider does make can be both intentional and momentary.

The Manual of Equitation of the French Army for 1912 states that "A good seat results from a general de-contraction, particularly from the suppleness of the loin... Fixity on horseback is the absence of all voluntary or useless movements and the reduction to the minimum of those that are indispensable." The reason to discover a quiet seat is so that we can listen. We must first find a place of quiet listening in order to act. Without listening, all of our actions are really reactions.

The task of the rider is to become aware of how his or her own actions cause reactions in the horse. The rider needs to discover a neutral place where she or he is not interfering with or disrupting the horse's balance. This is what a good seat is. If you act with the right hand and you don't know what the left is doing, you could be involuntarily asking for what you don't want. A horse cannot make these distinctions. A horse can only respond to your actions or not respond to your actions (the former being the most desirable, because that is where training begins). The more conscious each action becomes and the less a rider interferes, the more brilliantly the horse will move.

In learning to ride, a student needs to overcome his instinctive reflex responses and replace them with new patterns of learned responses. For example, a beginner needs to learn to sit up and not pull. All new riders (and quite a few experienced ones) have the overwhelming urge to lean forward and pull in the name of balance and control; yet because pulling and falling forward have disastrous effects on the balance of both horse and rider, this loss of control becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The rider's loss of balance reinforces his fear, and he then grabs on harder and leans further forward. It can become increasingly difficult for a rider to get out of this cycle. The only way to learn a different response is to make a change before this ingrained reaction kicks in.

One of the greatest aids in this process is what Alexander called "thinking in activity." By this he meant having a conscious awareness of what one is doing and, at the crucial moment before committing to the habitual reaction; making a clear decision to do something differently. The riding student must first be made aware of what is unconscious, and usually unnecessary and disruptive, movement Secondly, he must decide not to do that movement (i.e., lean forward when the horse increases in speed). And thirdly, he must allow his body to stay back. I use the word "allow" because if he muscularly forces himself to stay back he becomes instantly rigid and can no longer follow the movements of the horse.

The body responds to a given stimulus so quickly that we often react before we know we've reacted. To decide to change the course of things is no small charge. It requires exploring unknown territory. We cannot rely on former experiences and feelings, rather, we must rely on principles. If we rely solely on whether something "feels right," then we condemn ourselves to repeat the same habitual movements over and over again. "People don't do what they feel to be wrong when they are trying to be right" (Alexander, The Universal Constant in Living). Instead, we can learn to put our trust in our thinking, pausing instead of reacting, and deciding to follow a different course of action, regardless of how it might feel. In this way, we open the door to new possibilities. Alexander called this approach "keeping in touch with your reason."

If it is difficult to check one's reactions in general, it is nearly impossible when a person's or a horse's system is anything but calm. "In anxiety states, there is no such control: there is a state of tense preparedness which is liable to discharge excessively when the organism is stimulated; and in this state, all manner of aspects of the environment are noticed and reacted on, which would be ignored in a less tense state" (Frank Pierce Jones). Or, as Joyce Warrack said, "No instrument is as unmanageable as the human organism in a panic" (article: "The Indirect Approach to Singing"). Cultivating calmness is the task of both the rider and the trainer. Good humor is an invaluable aid. "Progress does not come from the movement itself but from the manner in which it is executed" (Manual of Equitation from the French Army, 1912).

Both the Alexander teacher and the rider communicate through the use of their hands. A beginner learns not to pull. An intermediate rider learns to leave his hands alone. An advanced rider learns to give with his hands. "Between fixed and pulling, there is a world" Nuno Oliveira). If I am not moving my hands in space, but I am still tensing every muscle in my forearm, it is still a pull. In describing the Alexander Technique's use of hands-on manipulations, Frank Pierce Jones, an early practitioner, said, "One of the basic principles of the technique seems to be that the amount of kinesthetic information conveyed is in indirect proportion to the force used in conveying it" This statement parallels Nuno Oliveira's description of using the hands in riding: "To fix is not pulled. It is adjusted. It remains tranquil. The hand has to be a filter, not a cork or an open faucet." Learning to give with the hands is a lifelong pursuit.

To pull or to push a horse into place constitutes force. Horses are no different than people in the fact that if one moves them with force, then they learn that it takes force to be moved. But if one asks with an ever-increasing delicacy, what we call "tact”, then we can communicate to the horse in the most refined and elegant ways. "The mark of good training," said Oliveira, "is the maximum each horse is capable of without force." The fact that a person does not need to employ force in order to ride is, for some reason, a very difficult concept for any of us to grasp. If a rider uses muscular force, the horse will meet that force with a corresponding resistance. This is a simple reflex: if you push against someone, he or she will push back; if you pull, he or she will pull back In addition, when the rider contracts the muscles of the leg to apply force, there is a disruption in the balance and ease of the seat.

Alexander maintained that "Man is a psycho-physical whole... he is a unified whole." Living creatures do not function in parts. The part is always a reflection of the entire system. In Basic Equitation, Commandant Jean Licart states, "It should be noted that because of the horse's muscular interrelationships, the forward and rear springs are in one piece. One of them can not be compressed without compressing the other; and if one of them is released, the other is too. We should not be so determined to get a specific result or movement that we compromise the use of ourselves or of our horses. "No matter how many specific ends you may gain, you are worse off than before, [Alexander] maintained, if in the process of gaining them you have destroyed the integrity of the organism" (Frank Pierce Jones). How we get somewhere is more important than whether or not we arrive.

In my experience, one of the benefits of studying the Alexander Technique and classical equitation simultaneously is that the principles of the two worlds reinforce each other. Riding from this approach becomes effortless. The horse and the rider learn to move with greater freedom. Lightness is a tangible and sustainable result.

When I apply the principles of the Alexander Technique, allowing my neck to be free in order to allow my head to move forward and up and my torso to lengthen and to widen, and if I include my limbs in this action, allowing my hands to move away from my back, the horse will have an immediate corresponding action, his back widening, his head releasing at the poll, his neck moving out with freedom. No matter how refined or complicated I become in my demands of the horse, if I return to this place of simplicity, the execution of the movement is done with ease and moves towards better integration for both of us. In addition, if the horse begins to drop his haunches underneath him and releases his jaw, his back becoming round, I experience the movement in my own body as though an Alexander teacher's hands were on me giving clear directions of energy moving up my spine, my head moving forward and up, and my back lengthening and widening.

Riding is "more about intelligence and feeling than muscle and strength" (Jean Saint-Fort Paillard, Understanding Equitation). The question is how small an effort can I make? The discovery is about the difference between control of movement and freedom of movement. The two studies continue to reinforce and illuminate each other. And in meeting the sensitivity of the horse, I find an ever-increasing delicacy and balance in myself so that the dialogue becomes a whisper, a thought a glance.

Elizabeth Reese is a graduate of the American Center for the Alexander Technique. She maintains a practice in Sugar Loaf, New York and in New York City where she is on faculty at ATNYC. She is also a student and teacher of classical equitation.

copyright 1995 Do not reprint without permission from the author.